- COVERS

The art and the times

- Wendi Song

The Macao Museum of Art is currently presenting the exhibition Language & the Art of Xu Bing – the largest solo exhibition ever held overseas by this internationally renowned artist.

Just one month before the leading Chinese contemporary artist Xu Bing’s first Macau solo exhibition opened, one of his masterpieces, A Case Study of Transference, was pulled by Guggenheim Museum from a highly anticipated exhibition in New York. The museum made the decision after coming under unrelenting pressure from animal rights supporters and critics over three works involving animals, including Xu’s piece in the exhibition Art and China after 1989. But for many artists, the museum’s decision is a major blow to artistic freedom and has resulted in strong criticism from the art world.

The original version of A Case Study of Transference from 1994 featured two pigs – a boar and a sow – having sex in front of audiences at one of the early informal art spaces in Beijing. The backs of the pigs were stamped with gibberish composed from the Roman alphabet and Xu’s invented Chinese characters, but most notably the work revealed an unexpected dynamic between the spectators and the spectacle. Despite concerns prior that the pigs might have “stage fright”, the result was the exact opposite with the pigs completely unfazed and the audience instead finding itself in an awkward position. The work highlighted the embarrassment and limitations that humans feel when faced with raw nature.

When he arrived in Macau recently, Xu, who was caught in the middle of the uproar, showed surprising calm towards this incident, perhaps because it was not the first time his work had been received in this way.

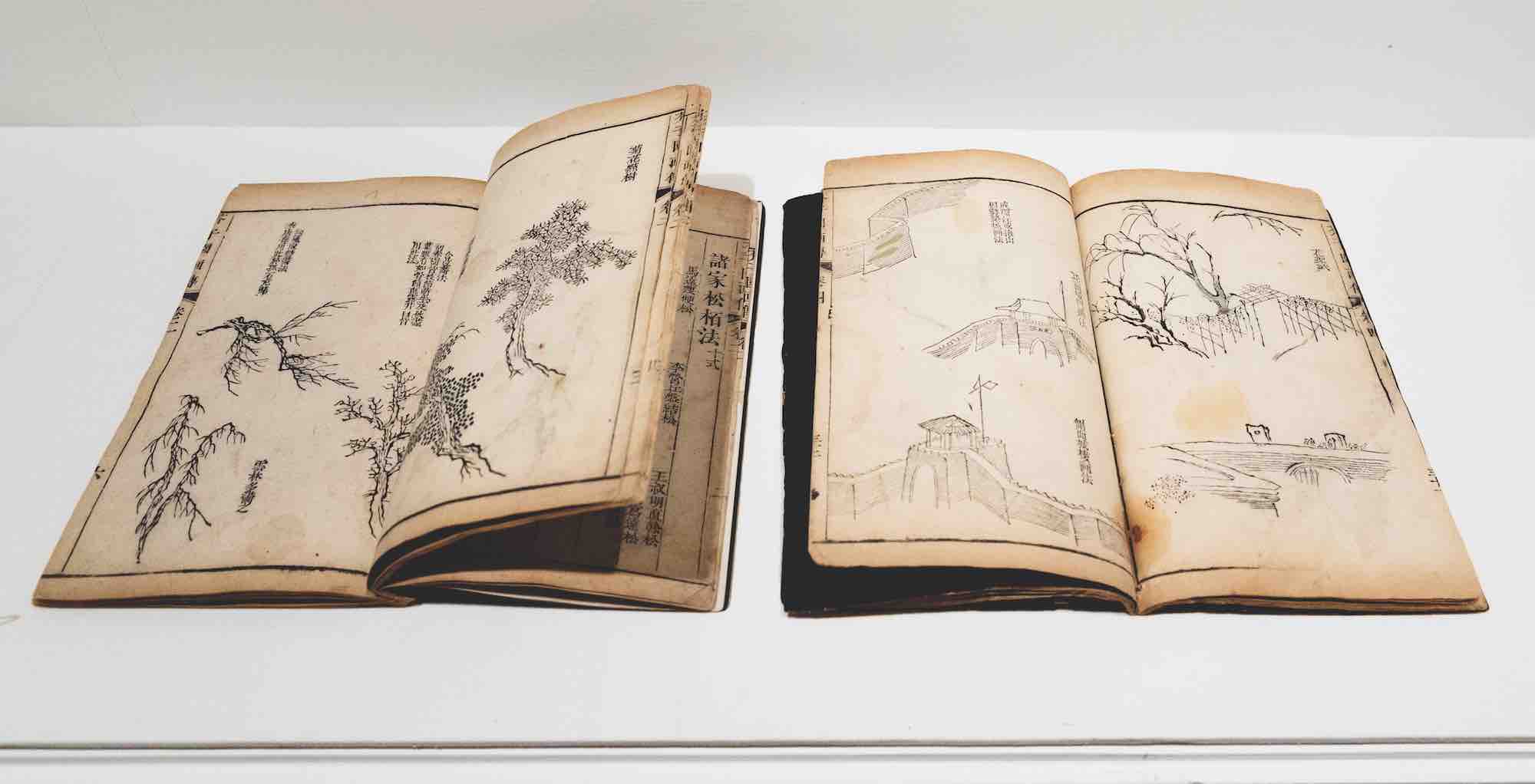

When Xu first exhibited his most renowned artwork, Book from the Sky, in 1988 in the National Art Museum of China, it provoked controversy both inside and outside China’s art world and was criticized by official Chinese media. However, it was this same work that quickly appeared in exhibitions overseas and allowed Xu Bing to rise in the international art world during the 1990s.

Xu mentioned this in a public talk in Macau.

“This fact actually made me rethink a lot,” he said. “Due to the political correctness of the United States in the field of animal protection, the freedom of expression of the artist has been limited. In fact, this could happen in any other place where local political correctness could limit your work. However, no matter where, one has to know how to use and convert this restriction to gain greater creativity and it is the artist’s ability to apply the restriction well.”

This actually represents Xu’s consistent creative attitude in that what he is concerned about most is not the art itself, but how to transform the energy of the “social scene” and the enlightenment of “social creativity” into the creation of art.

Born in 1955 in China, Xu is now a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing (CAFA), advising PhD students. He currently lives and works in both Beijing and New York. Solo exhibitions of his work have been held at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Louvre Museum in Paris, the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum amongst many other major institutions. Additionally, Xu has been invited to show his work at each of the 45th, 51st and 56th Venice Biennales and the Biennale of Sydney to name a few.

Over the last 30 years, Xu’s creative career has been interspersed with hybridism and multiplicity, and marked by an intense dedication to his studies and creativity revolving around language, which turns out to be the medium and subject matter of his artworks.

The exhibition Language & the Art of Xu Bing at the Macao Museum of Art brings together 30 of Xu’s significant works, along with other works of less intense scale, associated rough sketches and informative details, presenting a comprehensive train of thought about his language-themed original works. Among the exhibits are works rarely on display.

Covering an area of 1,350 square meters on three floors of the museum, the exhibition brings great visual impact. Viewers can take a close look at the important works of Xu as well as the logic and approach to language transformation through sketches and drafts.

During Xu’s short trip to Macau, High Life spoke with him several times and learned much about this great artist’s profound insights.

Xu Bing on language

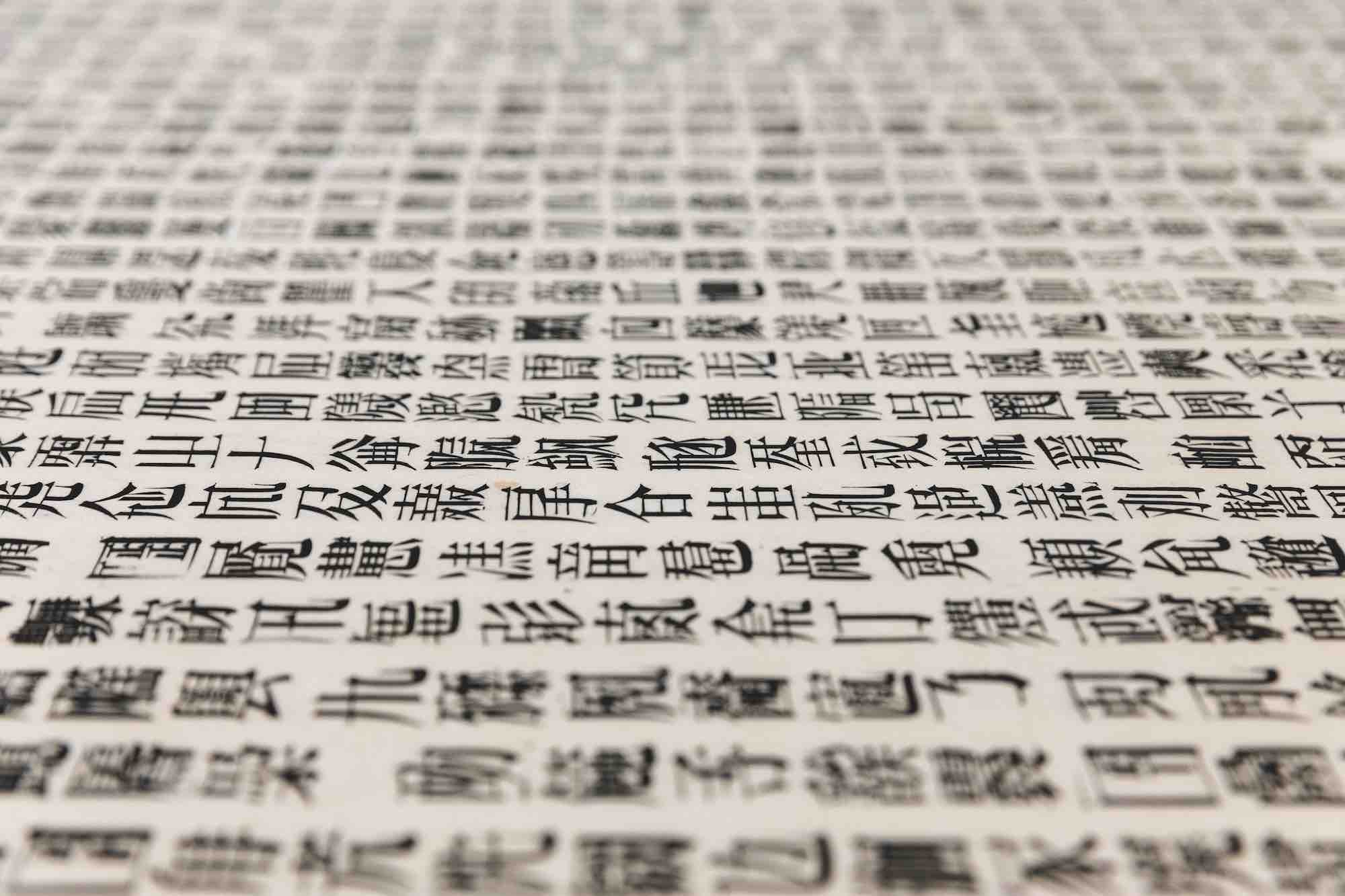

“First of all, what I have been using seems to be language but not its substantial essence. Language is like a type of implement to me: somehow, being used and consumed are its core function, even though its external packaging at times contains more cultural content. All of my works about language are actually all working on the packages.

“The reason that I consider the package to be more important is because Chinese characters are so special. The character of Chinese people or Chinese culture is deeply related to the character of Chinese characters.

“For instance, the ways of reading Chinese and English are so different. Though Chinese characters have been modernized as they went from pictographic to ideographic form, pictographic logic is still their underlying essence. For the modern Chinese character ‘ º® ’ (meaning ‘cold’), its form depicts a person wrapped in hay, curled up alone at home during the cold weather with the floor of the house covered in ice. There is already so much information embedded in just a single character like ‘cold.’ It affects our everyday life reading, thinking and observing in an intriguing manner.

“Although these works of mine are teasing and mocking the language, they actually hold it in awe as well. Our generation has experienced cultural revolution and lack of education, plus my parents work in Peking University, which led to an awkward relationship between the language and me.

“Generally, languages take effect through the conveyance of ideas, expression and communication. But for those of mine, they work through absence of communication, being misled and confusion. My ‘characters’ are not user-friendly fonts at all but more of a computer virus, capable of affecting the human mind. During the switch between being readable and unreadable in the mind of viewers and amidst the subversion of their preconceived notions, they upset viewers’ habitual ways of thinking and concepts of knowledge, obstruct viewers’ connectedness and impair their own expressiveness.

“They challenge the slothful minds of viewers. In the search for new grounds and ways of interpretation, they open up a wider, untapped cognitive space in viewers, putting them on alert against language and leading them to rediscover the primary sources of cognition. This is how my ‘characters’ work.

Xu Bing on creativity

“I returned to the city after the Cultural Revolution was over. I read whatever books fell my way and perused translation works of Western theories like many others. But all the readings made my thoughts unclear and I felt like something was lost. It’s like a starving man whose stomach hurts after eating too much all at once. Then I decided to make a book of my own to express this feeling.

“So I shut myself up in a small room and began to carve Book from the Sky (Xu’s book filled with glyphs designed to resemble Chinese characters) which is full of characters no one understands, including myself. It took around one year and I felt very comfortable doing it. When inventing and carving those fake characters that no one would understand, the touch of the knife and the fresh wood made me feel that I was really making progress.

“I later discovered that a person’s motivation for creation and life itself is to constantly look for such a special time period in which to do something special, to devote your life to this period to create so as to obtain a sense of presence and enrichment.

“It doesn’t matter what you do – it’s fine if it is not art – but the thing you do should be worth doing and be something no one has done before. It should also benefit society and be creative. These are my basic requirements.”

Xu Bing on Chinese contemporary art

“The rise of China’s economy for sure will contribute to the development of Chinese contemporary art and Chinese artists. Its marketization, market price and art price increase will actually arouse the world’s attention to Chinese contemporary art.

“However, the essence of the problem is actually the value of Chinese contemporary art. Due to the fast development of mankind including science and technology, our old doctrines and values are in fact beginning to collapse. At this juncture, China is rising. It is in fact in search of a new way of civilization.

“This is the reason I come back to China, because I really think China is a very experimental place. It gives us too much inspiration, too much possibility, too much space, but complicated problems as well. If China’s search can finally achieve success or obtain a result that would provide a reference and direction to civilization for the next stage in humanity, Chinese artists will become important at that time. But if we cannot find the way for the future of civilization, none of the Chinese artists will be important. Because the core of the art is not artwork.

“Why were the American artists of the last century so important? It’s because they, through their art, instructed and revealed the spirit of American civilization in the last century – and such civilization was important because it promoted the progress of civilization as a whole, therefore all their artists were important.

“For today’s artist, whoever can unveil the method and core spirit of today’s Chinese civilization as Andy Warhol revealed the spirit of American civilization of the last century, his art might matter. But that also depends on whether such a civilized exploration will be positive or not.”